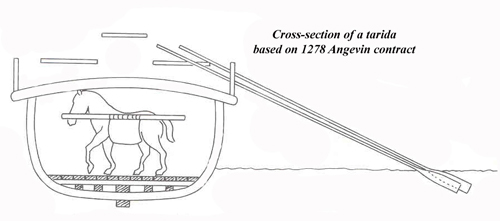

The Angevin contracts suggest that the tarida was very similar to the standard galley.

However, the fleet appears to have used them as support vessels and did not deploy

them with combat units. In fact, in all of the cases where the individual types of

ships can be identified where the fleet has been mustered for an operation, there is

no case of a tarida being included in the list of ships. Yet horse transports were

vital to the fleet raiding operations and for this reason, the office of the admiral

employed galeae apertae per puppa (galleys open in the stern). The fleet accounts always

distinguish between these vessels and taridas but unfortunately provide very little

information as to the exact differences.

no case of a tarida being included in the list of ships. Yet horse transports were

vital to the fleet raiding operations and for this reason, the office of the admiral

employed galeae apertae per puppa (galleys open in the stern). The fleet accounts always

distinguish between these vessels and taridas but unfortunately provide very little

information as to the exact differences.

The little information from the fleet accounts and the chronicles indicate that in many

aspects they were very similar. The galeae apertae in puppa had one hundred sixteen

oars, which is slightly more than the one hundred eight or one hundred twelve oars

carried by the taridas in the Angevin contracts. These galleys carried a complement of

officers, pilots, and crossbowmen identical to the galleys of one hundred twenty oars,

which suggests that they were armed to fight with the other galleys in the fleet.

Unfortunately, there are no further details in the accounts concerning these vessels

and the number of horses they could carry. Muntaner repeatedly speaks of the need for

the fleet to have open-stern galleys, and in one instance gives some detail as to the

number of horses that could be carried. Muntaner describes how twenty galleys ‘obertes

per popa’ were loaded with four hundred mounted knights and ‘many almugavars’. Based

on his description, this would have meant that each galley ‘open through the stern’

had a capacity of twenty horses. In another case, the Angevins raided Augusta with

twenty galleys ‘open through the stern’ carrying three hundred mounted knights, which

means each galley carried fifteen horses.

Unfortunately, there are no further details in the accounts concerning these vessels

and the number of horses they could carry. Muntaner repeatedly speaks of the need for

the fleet to have open-stern galleys, and in one instance gives some detail as to the

number of horses that could be carried. Muntaner describes how twenty galleys ‘obertes

per popa’ were loaded with four hundred mounted knights and ‘many almugavars’. Based

on his description, this would have meant that each galley ‘open through the stern’

had a capacity of twenty horses. In another case, the Angevins raided Augusta with

twenty galleys ‘open through the stern’ carrying three hundred mounted knights, which

means each galley carried fifteen horses.

Often the galea aperta in puppa are simply listed as galleys in the fleet accounts suggests that they were considered fighting vessels first and transports second, unlike the taridas which were basically considered transports. Analysis of the Angevin contracts for taridas also indicates that these vessels were not constructed with the necessary strength or superstructure forward required of large combat vessels. The advantage of these galleys was that they could unload horses and their riders directly from the stern on to the beach via a ramp, much like a modern landing craft (see Turkish transport image). The ability of these vessels to act as combatants and still carry a significant number of cavalry provided the fleet with a tactical flexibility it would not have had using a merchant ship.

The transportation of horses required a great deal of planning and expertise.

Horses are susceptible to seasickness, and the crews had to be careful in how the

animals were placed in the vessel and how they were fed. The horses were supported

by canvas slings to prevent the horses from being injured due to excessive rolling.

The slings also acted as gimbals to keep the animals vertical and decrease the effects

of seasickness. The holds also were covered to provide some traction for the horses

on the deck and, more importantly, to absorb the waste produced by twenty horses.

As with their Angevin counterparts, the horses were fed barley and hay.

The feeding required no small amount care, for overfeeding horses that are

unable to exercise can quickly lead to severe intestinal disorders.

The successful transport of horses by sea over long distances was an art acquired

by hard lessons learned during the First and Third Crusades,

but by the late thirteenth century the technique appears to have been perfected.

Considering that the fleet transported hundreds of horses between Sicily, Calabria,

and North Africa on a regular basis, there are only four cases in all of the accounts

of horses dying at sea.

As with their Angevin counterparts, the horses were fed barley and hay.

The feeding required no small amount care, for overfeeding horses that are

unable to exercise can quickly lead to severe intestinal disorders.

The successful transport of horses by sea over long distances was an art acquired

by hard lessons learned during the First and Third Crusades,

but by the late thirteenth century the technique appears to have been perfected.

Considering that the fleet transported hundreds of horses between Sicily, Calabria,

and North Africa on a regular basis, there are only four cases in all of the accounts

of horses dying at sea.

The perfection of horse transportation combined with the galea aperta per puppa allowed the Catalan-Aragonese fleet to deploy significant land units with virtually no warning against the enemy. The advantage this gave the fleet was not lost on the admiral, and he put it to good use, much to the grief of both the Angevins and the Moslems of North Africa.

For more on the evolution of horse transports and tarida construction see:

Pryor, John. “The transportation of horses by sea during the era of the Crusades:

Eighth century to 1285 A.D.” Mariner’s Mirror 68 (1982): 9-27, 103-129.

Tarida cross-section from this article.

Pryor, John. “The naval architecture of crusader transport ships and horse transports

revisited.” Mariner’s Mirror 76 (1990): 255-273.