The medieval crossbow was one feared weapons on the battle field. Partly because of

the exaggerated status of the English longbow, the crossbow has earned a undeservedly

poor reputation. In fact it had much more widespread use than the typical warbow and was

particularly useful at sea. It had the advantage that one could learn to use it in a

relatively short time compared to someone using a longbow, which took years to become proficient.

This has led some to assume that the crossbow was an inferior weapon. Contrary to popular belief,

as the passage on Catalan crossbowmen on the pervious page points out, to be

truly profiecent required practice. The true professionals, such as the Catalans, also

were proficient at making and repairing their weapons.

poor reputation. In fact it had much more widespread use than the typical warbow and was

particularly useful at sea. It had the advantage that one could learn to use it in a

relatively short time compared to someone using a longbow, which took years to become proficient.

This has led some to assume that the crossbow was an inferior weapon. Contrary to popular belief,

as the passage on Catalan crossbowmen on the pervious page points out, to be

truly profiecent required practice. The true professionals, such as the Catalans, also

were proficient at making and repairing their weapons.

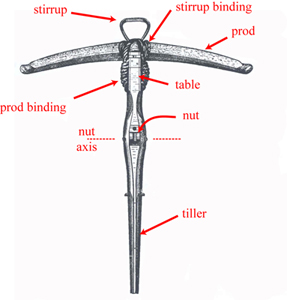

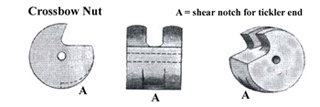

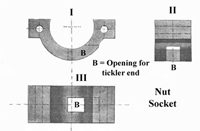

As can be seen in diagams the actual mechanism was relatively simple and robust. The typical 13th century crossbow consisted to the bow or 'prod' lashed to the end of the 'tiller' which housed the trigger mechism. The mechanism was a notched cylinder (see figures) with a catch or 'shear notch' cut into it to catch the end of the trigger or 'tickler'. The two upturned prongs on the cylinder or 'nut' held the bowstring until the 'tickler' was pulled, allowing the 'nut' to rotate forward releasing the bowstring. (see animation below).

Fleet regulations required the Catalan marine crossbowmen to carry a 'one-foot' and 'two-foot' crossbow. The 'two-foot'

meant it took both feet to cock or

'span' the crossbow. These larger bows may well have been composite crossbows. Composites had 'prods' made of

layers of wood and sinew to make them stronger and flexible. The problem with composites,

and with bowstrings also, was that at sea if they got wet they would loose their strength

and can actually come apart. The crossbowmen tried to prevent this by covering the 'prods' and

strings with varnishes and glues.

and with bowstrings also, was that at sea if they got wet they would loose their strength

and can actually come apart. The crossbowmen tried to prevent this by covering the 'prods' and

strings with varnishes and glues.

While the crossbow did not have the range of a longbow, 200 yards maximum for this period, they had tremendous hitting power at closer ranges, which was an advantage in the close quarters at which naval battles were fought at this time. To withstand the sudden force applied on firing, the arrows, known as bolts or quarrels, had to much stronger than the typical arrow thus the short, fat shafts. The quills were made of feathers, wood or leather. The fleet went through prodigious amounts of quarrels, with the arsenal at Messina making over 100,000 bolts in one year alone.