Probably the most important, and certainly most celebrated, members of the fleet were

the balistarii Catalani, or Catalan crossbowmen. The crossbow is mentioned as far back

as the 5th century B.C. in Greece, but did not become widespread in Europe until the 11th century.

Because they were so deadly against knights, Pope Innocent II and the

Church of the Lateran Council issued a judgement in 1139 against the use of the crossbow by Christians against Christians.

The medieval crossbow was referred to as "the deadly art of crossbowmen, hated by God,..."

The Catalan crossbowmen  were considered the best in the Mediterranean, the Genoese not withstanding. The men

were recruited from throughout Catalonia and Valencia. Many were undoubtedly veterans

of the mudéjar uprising of 1276 and the border skirmishes with Castile. Most of what

is known of them comes from Muntaner, who wrote:

were considered the best in the Mediterranean, the Genoese not withstanding. The men

were recruited from throughout Catalonia and Valencia. Many were undoubtedly veterans

of the mudéjar uprising of 1276 and the border skirmishes with Castile. Most of what

is known of them comes from Muntaner, who wrote:

“The Catalans are the best, in that they know how to make a crossbow, and each knows how to adjust his crossbow, and knows how to make a bolt, and a nut for the cord, and to string it, and to fasten it, and all that pertains to a crossbow; and the Catalans do not understand how anyone could be a crossbowman if he did not know, from beginning to end, all that pertains to the crossbow. And so they carry all their tools in a box, as if they had a crossbow workshop, and no other people do this. The Catalans learn this while drinking their mother’s milk, and the other people of the world do not do this; that is why the Catalans are the supreme crossbowmen of the world. And because of this, the admirals and captains of the Catalan fleets should give all attention that this singular ability, which is not in other nations, that they do not lose it and that they practice it.” (Click Here to learn more about crossbow construction.)

While this may appear an exaggeration, the office of the admiral went out of its way to recruit men from Catalonia to man the galleys. The accounts repeatedly note that when 'Latin crossbowmen' were recruited it was ‘due to a lack of’ available Catalan ones. The office of the admiral spent a great deal of time and money ferrying Catalan balistarii from Catalonia to Sicily. That the fleet expended so much time and money to recruit from Catalonia indicates that the Catalan recruits were enough of an asset to the fleet to warrant the effort. The fact that the crossbowmen serving on galleys were paid at the same rate as the nauclerii is another indication of their importance. However, there is no evidence that the 'Latin crossbowmen' were paid any less than the Catalan ones.

The office of the admiral valued these men highly and when the enemy captured them,

the crossbowmen were ransomed back. These men were held and

not executed, indicating that the Angevins were aware of their value to the Crown of

Aragon and took advantage of it,  since the normal fate of the common solider

or sailor was death or maiming by having a hand amputated. In 1286, the fleet paid the considerable sum of

one ounce of gold per man to liberate ten Catalan crossbowmen from the Angevins.

since the normal fate of the common solider

or sailor was death or maiming by having a hand amputated. In 1286, the fleet paid the considerable sum of

one ounce of gold per man to liberate ten Catalan crossbowmen from the Angevins.

While the accounts do not specify armaments for the other members of the crew, they specify how the crossbowmen were armed. Each man had a cuirass, an iron cap, a collar, shoulder armor, and a short sword. His main armament consisted of two ‘crossbows of two feet’ and one ‘crossbow of one foot’, along with three hundred bolts for each type of crossbow. The feet were required to cock the weapon. Based on medieval iconography, the two-foot crossbow required the user to sit down to cock, though this would be impractical on the crowded deck of a galley in the middle of a battle. The men probably used a 'crow's foot' (belt claw) to bend the 'prod', or 'lath', of the crossbow as seen in medieval iconography of that time. The crow's foot was a hook hung on a belt. The balistario hooked the bow string in it and put his foot in stirup and pushed down with his foot. A 'two-foot' bow probably required the man to crouch to engage the hook and then to standup. The weapon fired a substantially different bolt from the one-foot variety of weapon, as the account makes clear that crossbowman needed bolts made specifically for each type of crossbow. Iconography form the Cantigas de Santa Maria suggests the 'two-foot' crossbow may have been a composite bow made of laminated wood and sinew, while the 'one-foot' bow probably had just a solid wood 'prod'.

As with nauclerii, pay for crossbowmen depended on experience and duty, and ranged from ten to eighteen tareni per month. The standard pay for crossbowmen on galleys was eighteen tareni, but the rate could vary. The crossbowmen not only manned the galleys, but also were assigned to the frontier castles in Calabria under the control of the admiral. In fact, all examples of pay below the standard fleet pay are found in similar account entries where the crossbowmen were assigned to castles. This suggests that the difference in pay between the higher eighteen tareni and the lower rates of fifteen or ten tareni per month was hardship or hazardous duty pay for service in the fleet.

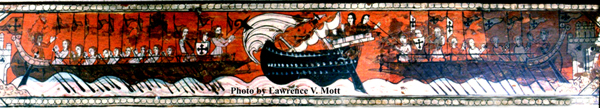

Pictures from the Cantigas de Santa Maria are courtsey of the Patriomonio Nacional de España.