The events that eventually brought the Crown of Aragon into direct

conflict with the Count of Anjou and the papacy originated with the long

struggle between various popes and the House of Hohenstaufen for control

of Italy and Sicily. While on the face of it, the events which occurred

after the death of Frederick II would seem to have little connection with

what was transpiring on the Iberian Peninsula, in fact, the very success

of the papacy and Charles of Anjou against the Hohenstaufens created a

situation which virtually assured that the two ascendant powers in the

Western Mediterranean would eventually collide. In order to understand the

involvement of the Crown of Aragon in Sicily the relationship of Charles

of Anjou and the papacy has to be examined.

that eventually brought the Crown of Aragon into direct

conflict with the Count of Anjou and the papacy originated with the long

struggle between various popes and the House of Hohenstaufen for control

of Italy and Sicily. While on the face of it, the events which occurred

after the death of Frederick II would seem to have little connection with

what was transpiring on the Iberian Peninsula, in fact, the very success

of the papacy and Charles of Anjou against the Hohenstaufens created a

situation which virtually assured that the two ascendant powers in the

Western Mediterranean would eventually collide. In order to understand the

involvement of the Crown of Aragon in Sicily the relationship of Charles

of Anjou and the papacy has to be examined.

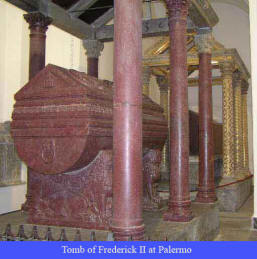

When Frederick II (left), Holy Roman Emperor, died

in December of 1250, Pope Innocent IV had every reason to rejoice.

Frederick had represented a real threat to the papacy ever since he became

emperor in 1220 over the objections of Pope Honorius III. The various

popes who had combated the Hohenstaufens had seen the holding of both the

Kingdom of Sicily,

together with Lombardy and Germany, as both a direct

threat and usurpation. With the Papal States hemmed in by the Emperor's

holdings and confronted with the resources the wealth of those lands could

purchase, the papacy feared that the Emperor was in a position to crush

the Holy See and return it to the state of submission to the Holy Roman

Emperors which had existed prior to the reform of the church in the

eleventh century. Moreover, the Kingdom of Sicily, or Regno, was seen as

being part of the Holy See due to the homage and fealty Pope Anacletus

received from Roger II for granting him the crown of the Kingdom of

Sicily, Calabria,

and Apulia in 1130. The Hohenstaufens had refused to

acknowledge that the Kingdom of Sicily was a vassal state of St. Peter,

and this, coupled with the immediate threat of encirclement, had resulted

in continual papal hostility. Thus, when Frederick II died in 1250, Pope

Innocent IV had reason to be pleased as it meant that one of the papacy's

most tenacious adversaries had been removed.

Frederick had represented a real threat to the papacy ever since he became

emperor in 1220 over the objections of Pope Honorius III. The various

popes who had combated the Hohenstaufens had seen the holding of both the

Kingdom of Sicily,

together with Lombardy and Germany, as both a direct

threat and usurpation. With the Papal States hemmed in by the Emperor's

holdings and confronted with the resources the wealth of those lands could

purchase, the papacy feared that the Emperor was in a position to crush

the Holy See and return it to the state of submission to the Holy Roman

Emperors which had existed prior to the reform of the church in the

eleventh century. Moreover, the Kingdom of Sicily, or Regno, was seen as

being part of the Holy See due to the homage and fealty Pope Anacletus

received from Roger II for granting him the crown of the Kingdom of

Sicily, Calabria,

and Apulia in 1130. The Hohenstaufens had refused to

acknowledge that the Kingdom of Sicily was a vassal state of St. Peter,

and this, coupled with the immediate threat of encirclement, had resulted

in continual papal hostility. Thus, when Frederick II died in 1250, Pope

Innocent IV had reason to be pleased as it meant that one of the papacy's

most tenacious adversaries had been removed.

However, Frederick's death did not remove the threat to the

Holy See nor did it bring the Kingdom of

Sicily under papal control. If Innocent IV hoped to take advantage of the

situation, he was to be greatly disappointed. Conrad IV, Frederick's

eldest surviving legitimate son, moved swiftly, not only to gain the title

of emperor but also to enter northern Italy and consolidate his power

there. Innocent tried to outmaneuver Conrad and split Sicily from him by

offering the kingdom to Conrad's younger half-brother Henry, but this came

to naught. Despite efforts by Conrad to reconcile with Innocent IV,

relations had swiftly deteriorated to the point that by January 1254 the

pope had excommunicated Conrad and was preaching a crusade against him,

just as he done against his father. Despite this, Conrad proved a

successful commander and, backed by money generated from taxes imposed in

the kingdom, he was a position to pose a serious threat to the papacy.

However, just as the pope was facing what appeared to be major crisis, in

April 1254 Conrad fell suddenly ill and died. This unexpected change of

fortune presented Innocent IV with an opportunity to split the Kingdom of

Sicily from Germany, and he moved swiftly to take advantage of the

situation.

However, Frederick's death did not remove the threat to the

Holy See nor did it bring the Kingdom of

Sicily under papal control. If Innocent IV hoped to take advantage of the

situation, he was to be greatly disappointed. Conrad IV, Frederick's

eldest surviving legitimate son, moved swiftly, not only to gain the title

of emperor but also to enter northern Italy and consolidate his power

there. Innocent tried to outmaneuver Conrad and split Sicily from him by

offering the kingdom to Conrad's younger half-brother Henry, but this came

to naught. Despite efforts by Conrad to reconcile with Innocent IV,

relations had swiftly deteriorated to the point that by January 1254 the

pope had excommunicated Conrad and was preaching a crusade against him,

just as he done against his father. Despite this, Conrad proved a

successful commander and, backed by money generated from taxes imposed in

the kingdom, he was a position to pose a serious threat to the papacy.

However, just as the pope was facing what appeared to be major crisis, in

April 1254 Conrad fell suddenly ill and died. This unexpected change of

fortune presented Innocent IV with an opportunity to split the Kingdom of

Sicily from Germany, and he moved swiftly to take advantage of the

situation.