The removal of the last Hohenstaufen claimant to the Kingdom of Sicily not

only allowed Charles to tighten his hold on the region, but also permitted

him to pursue another project that he had been developing. Since 1267

Charles had been preparing to launch an expedition against Constantinople

in order to restore the Latin Empire there, which had been lost in 1261.

However, the invasion of Conradin in 1268 had spared the Byzantine Emperor

Michael Palaeologus from Charles's attentions. By 1270 Charles was ready

to try again but now another distraction appeared.

His brother, Louis IX, was determined to go on crusade again, despite the

previous fiasco in Egypt (1249 - 1252), and asked Charles to support him.

It seems clear that Charles was less than enthusiastic about the venture

but had decided to make the best of the situation. Over the objections of

his councilors, Louis permitted himself to be persuaded by Charles that a

crusade against Tunis was a better alternative than one directed towards

Jerusalem. The Kingdom of Tunis, which had been obligated since 1158 to

pay tribute to the King of Sicily, had used the death of Manfred as an

excuse to stop payments. Charles saw the crusade as an opportunity to

reinstate his authority in Tunis while fulfilling his obligation to go on

crusade with his brother. Even then, Charles did not directly participate

in the fighting until the Christian forces were in complete disarray, and

his presence was demanded. Yet the result was not a decisive victory for

the crusaders, primarily due to the death of Louis IX. The crusade finally

ended in a negotiated peace that, other than paying for the expenses of

the other crusaders, essentially benefited Charles. Among other things it

restored the tribute to Charles and allowed his merchants free access to

Tunis. The treaty was to last ten years but was renewed in 1280. However,

Charles's ambitions in the Maghreb would bring his commercial interests

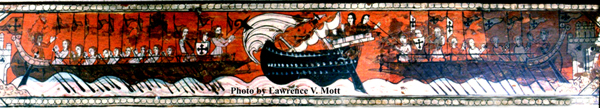

into conflict with another maritime power in the region. The miniature at

the right depicts Charles of Anjou receiving ambassadors from Tunis (Bibliothèque

Nationale, Paris, France).

His brother, Louis IX, was determined to go on crusade again, despite the

previous fiasco in Egypt (1249 - 1252), and asked Charles to support him.

It seems clear that Charles was less than enthusiastic about the venture

but had decided to make the best of the situation. Over the objections of

his councilors, Louis permitted himself to be persuaded by Charles that a

crusade against Tunis was a better alternative than one directed towards

Jerusalem. The Kingdom of Tunis, which had been obligated since 1158 to

pay tribute to the King of Sicily, had used the death of Manfred as an

excuse to stop payments. Charles saw the crusade as an opportunity to

reinstate his authority in Tunis while fulfilling his obligation to go on

crusade with his brother. Even then, Charles did not directly participate

in the fighting until the Christian forces were in complete disarray, and

his presence was demanded. Yet the result was not a decisive victory for

the crusaders, primarily due to the death of Louis IX. The crusade finally

ended in a negotiated peace that, other than paying for the expenses of

the other crusaders, essentially benefited Charles. Among other things it

restored the tribute to Charles and allowed his merchants free access to

Tunis. The treaty was to last ten years but was renewed in 1280. However,

Charles's ambitions in the Maghreb would bring his commercial interests

into conflict with another maritime power in the region. The miniature at

the right depicts Charles of Anjou receiving ambassadors from Tunis (Bibliothèque

Nationale, Paris, France).