The man whom Urban IV chose to rid the papacy of Manfred has

been portrayed as either the consummate medieval statesman or the devil

incarnate, depending on the nationality of the author. Charles of Anjou

has been vilified by German authors for executing the young Conradin

in 1266, while Italian authors have portrayed him as a cruel oppressor who

was sucking the life out of the Kingdom of Sicily. The French authors in

defense of Charles point out that he was in fact an efficient and

beneficent ruler, if somewhat ambitious. They argue that Charles brought

efficient government to the areas he ruled and administered justice in an

impartial and exemplary manner. What does appear clear, from his handling

of his estates in France to his later schemes with regards to the

Byzantine Empire, is that Charles was extremely ambitious and willing to

take advantage of any situation that presented itself. While there is no

doubt he was a pious man, he saw himself more as an independent instrument

of God and he was not one to let himself be manipulated by a pope. He was

also a meticulous planner and a supreme organizer. However, this penchant

towards organizing his holdings so that he could extract the maximum

benefit from them did not endear him to his subjects.

doubt he was a pious man, he saw himself more as an independent instrument

of God and he was not one to let himself be manipulated by a pope. He was

also a meticulous planner and a supreme organizer. However, this penchant

towards organizing his holdings so that he could extract the maximum

benefit from them did not endear him to his subjects.

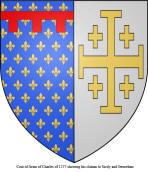

Charles was born in 1227 as the youngest brother of Louis IX and is described as having grown up in rather loveless surroundings at the court. However, Charles also received an outstanding education and, being at the center of the Capetian court, obtained firsthand experience in governmental affairs. Moreover, his family did arrange for the young Charles to come into possession of some of the most important territories in France, either through inheritance or marriage. At the age of twenty, he was enfeoffed with the important counties of Anjou and Maine. More importantly, by way of marriage to Beatrice of Provence, he had come into possession of the rich lands of Provence in 1246, and he moved swiftly to exert his command over the region. It is here that a pattern of control appears that Charles would use again in Sicily with disastrous results.The coat of arms to the left shows his pretensions. The left half is the coat of arms for Sicily and the right half or the Kingdom of Jerusalem, which he bought in 1277.

Almost immediately, Charles began to place French lawyers and

administrators in the offices of the county and to demand his rights as

overlord of the region. It was not that Charles was asking for rights and

dues that were not legally his, but the Provençals were not accustomed to

the rather efficient manner in which the Angevin officials went about

enforcing them. In 1251 Charles was forced to put down a revolt at Arles,

Avignon, and Marseilles and had to return in 1256 to suppress another

uprising at Marseilles when he finally stripped the city of its political

power and replaced the city officials with his own. His problems there

would not end until he crushed further conspiracies and revolts in 1262

and 1263. It was at this time that he began to turn the city into a major

naval base. While the Angevin administration of the city would generally

prove beneficial until the War of the Sicilian Vespers, the causes for the

initial revolt seem to have escaped Charles. He simply did not appear realize

that it had been the manner in which he had

imposed his government on the populace that had triggered the revolts,

not the government itself. While Charles had been able to suppress the

Provençal revolts, he would not have the same good fortune in dealing

with the Sicilians.

Almost immediately, Charles began to place French lawyers and

administrators in the offices of the county and to demand his rights as

overlord of the region. It was not that Charles was asking for rights and

dues that were not legally his, but the Provençals were not accustomed to

the rather efficient manner in which the Angevin officials went about

enforcing them. In 1251 Charles was forced to put down a revolt at Arles,

Avignon, and Marseilles and had to return in 1256 to suppress another

uprising at Marseilles when he finally stripped the city of its political

power and replaced the city officials with his own. His problems there

would not end until he crushed further conspiracies and revolts in 1262

and 1263. It was at this time that he began to turn the city into a major

naval base. While the Angevin administration of the city would generally

prove beneficial until the War of the Sicilian Vespers, the causes for the

initial revolt seem to have escaped Charles. He simply did not appear realize

that it had been the manner in which he had

imposed his government on the populace that had triggered the revolts,

not the government itself. While Charles had been able to suppress the

Provençal revolts, he would not have the same good fortune in dealing

with the Sicilians.

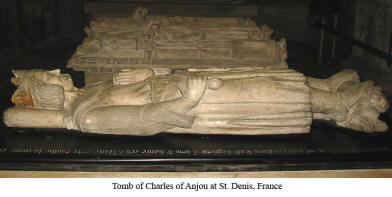

Charles would suffer a

series of defeats at the hands of Roger

of Lauria following the revolt of Sicily in April 1282. Yet despite losses

at the Battle of Malta in 1283 and the Battle of Naples in 1284, he continued in his efforts to

regain Sicily and planned a crusade against Aragon in 1285. He would never

see the fruition of his efforts or the defeat of his archrival Peter III

of Aragon. In December 1284 Charles was traveling through the eastern section of

Apulia

trying to reorganize his forces at Brindisi and elsewhere for

another effort when he became ill and finally died on

January 7th, 1285, in the town of Foggia. He was initially buried at

Naples, but Robert II later moved his remains to the Basilica of St.

Denis in France.

Charles would suffer a

series of defeats at the hands of Roger

of Lauria following the revolt of Sicily in April 1282. Yet despite losses

at the Battle of Malta in 1283 and the Battle of Naples in 1284, he continued in his efforts to

regain Sicily and planned a crusade against Aragon in 1285. He would never

see the fruition of his efforts or the defeat of his archrival Peter III

of Aragon. In December 1284 Charles was traveling through the eastern section of

Apulia

trying to reorganize his forces at Brindisi and elsewhere for

another effort when he became ill and finally died on

January 7th, 1285, in the town of Foggia. He was initially buried at

Naples, but Robert II later moved his remains to the Basilica of St.

Denis in France.

Charles would be followed by his son Charles of Salerno, who would become Charles II of Anjou (1285 -1309).