Despite the death of Charles of

Anjou, preparations continued in France for the crusade against Aragon.

Neither the Angevin losses nor the death of Charles deterred Philip III

from preparing a naval force to support the crusade called by Pope Martin

IV against Peter III and the Aragon for their attempts to control Sicily

in opposition to papal wishes. Philip III had already agreed to undertake the crusade in February 1284 after

some extended haggling with the papacy concerning the nature of the grant

of Aragon to Philip's son and the amount of money the church would

donate to the crusade. Once terms were agreed on, Philip III had moved

swiftly and by May 1285 had marshaled an army of 8,000. Philip was aware that

Peter III was mired in political

problems at home. The death of Pope Martin IV

on March 29, 1285 had been a minor setback,

but by then Philip III already had received the pledge of all of the

tithes of the church in France in support of the crusade.

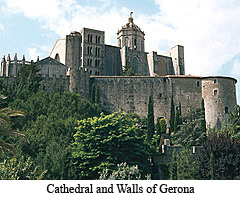

Philip planned to move south

into Catalonia and capture first Gerona and then Barcelona before Peter

could muster any effective resistance or receive help from Sicily.

Because of the terrain, the French were forced to supply the

army by sea, and they proceeded to establish a string of bases from

Marseilles to Rosas on the

Catalan

coast. Located only twenty miles from

Gerona, Rosas became the lynch pin of French campaign. The importance of

maintaining control of the sea was not lost on Philip III, and

approximately one quarter of the money raised for the crusade went to

support the fleet. The

chronicles are hopelessly confused about the size of the fleet, but it

appears that Philip had collected approximately 210 ships, of which at

least 100 were galleys.

III had already agreed to undertake the crusade in February 1284 after

some extended haggling with the papacy concerning the nature of the grant

of Aragon to Philip's son and the amount of money the church would

donate to the crusade. Once terms were agreed on, Philip III had moved

swiftly and by May 1285 had marshaled an army of 8,000. Philip was aware that

Peter III was mired in political

problems at home. The death of Pope Martin IV

on March 29, 1285 had been a minor setback,

but by then Philip III already had received the pledge of all of the

tithes of the church in France in support of the crusade.

Philip planned to move south

into Catalonia and capture first Gerona and then Barcelona before Peter

could muster any effective resistance or receive help from Sicily.

Because of the terrain, the French were forced to supply the

army by sea, and they proceeded to establish a string of bases from

Marseilles to Rosas on the

Catalan

coast. Located only twenty miles from

Gerona, Rosas became the lynch pin of French campaign. The importance of

maintaining control of the sea was not lost on Philip III, and

approximately one quarter of the money raised for the crusade went to

support the fleet. The

chronicles are hopelessly confused about the size of the fleet, but it

appears that Philip had collected approximately 210 ships, of which at

least 100 were galleys.

On paper, the Capetian fleet appears to have been highly formidable and the loss of ships during the last two years would seem to have had little effect on the overall strategic picture. However, the early battles had bled the region of its experienced admirals, marines, rowers, captains, and seamen. The upshot was that the French fleet was manned by inexperienced marines and sailors who had little or no combat experience. Moreover, it was led by William of Lodève who had little naval experience and would prove as incapable of dealing with the Catalans as his predecessor Henry of Nice.

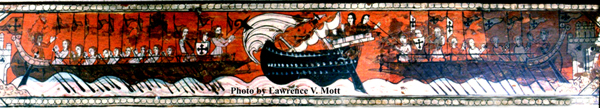

The crusade began with Philip III moving against Rousillon in June and with the help of King James of Mallorca he moved to occupy Perpignan and Elne. The French then moved across the Pyrenees and laid siege to Gerona. Peter harassed the French as best he could, but his army was too small to challenge Philip effectively. The French probably had expected a quick siege, but Gerona would hold out until September 7th. During those three months of siege (13th century fresco of siege on the left), the hot weather and unsanitary conditions led to an outbreak of disease that not only ravaged the besiegers but also spread to the fleet at Rosas.