In December 1293, James II and

Charles II met at Figueras and signed a preliminary document in which

James agreed to relinquish his claim to Sicily in return for compensation.

This treaty effectively brought operations by the Catalan-Aragonese fleet

to an end since any attacks against the Regno were prohibited. By 1294

Charles had forced the election of a new pope, Celestine V, but the

saintly man could not bear the weight of the office and resigned in

December 1294. However, the new pope, Boniface VIII was ready to bring the

conflict to a resolution and on June 12, 1295 at the birthplace of the pope

the Treaty of Anagni was signed. In it James II agreed

to give up Sicily, return the hostage sons of Charles and moreover to

return Mallorca to his uncle James, the former king of the island. For his

part, James received Sardinia and the daughter of Charles II in marriage

along with a substantial dowry provided by the Church. Pope Boniface in

turn agreed to lift all sanctions against Aragon and Sicily. While the

peace was designed to satisfy the papacy, France and Aragon,

Prince

Frederick, much less the Sicilians, had not been consulted. In an effort to persuade Frederick to accept the agreement,

Boniface VIII met with him at Velletri and

offered Frederick marriage to Catherine of Courtenay, who

was the technical heiress to Constantinople, and generous

support from the church for a future crusade against Constantinople.

his claim to Sicily in return for compensation.

This treaty effectively brought operations by the Catalan-Aragonese fleet

to an end since any attacks against the Regno were prohibited. By 1294

Charles had forced the election of a new pope, Celestine V, but the

saintly man could not bear the weight of the office and resigned in

December 1294. However, the new pope, Boniface VIII was ready to bring the

conflict to a resolution and on June 12, 1295 at the birthplace of the pope

the Treaty of Anagni was signed. In it James II agreed

to give up Sicily, return the hostage sons of Charles and moreover to

return Mallorca to his uncle James, the former king of the island. For his

part, James received Sardinia and the daughter of Charles II in marriage

along with a substantial dowry provided by the Church. Pope Boniface in

turn agreed to lift all sanctions against Aragon and Sicily. While the

peace was designed to satisfy the papacy, France and Aragon,

Prince

Frederick, much less the Sicilians, had not been consulted. In an effort to persuade Frederick to accept the agreement,

Boniface VIII met with him at Velletri and

offered Frederick marriage to Catherine of Courtenay, who

was the technical heiress to Constantinople, and generous

support from the church for a future crusade against Constantinople.

Boniface VIII had hoped to use the treaty to separate Sicily from the Angevins and bring it back under papal control with the proposed marrriage of Catherine of Courtenay. Aside from the fact that Catherine refused the marriage, the Sicilians made it clear they would not accept any agreement that might lead to Angevin rule again and begged Frederick to become their king. On December 12, 1295 he was crowned Frederick III at Palermo, despite papal threats. Frederick III was at once excommunicated and the island placed under interdict, neither of which bothered the king nor his people. The following year of 1296 entailed diplomatic maneuvering in attempt to entice Frederick to give up Sicily.

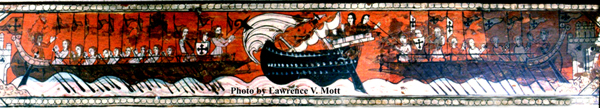

It was sometime during this period that a portion of the Catalan-Aragonese fleet left Sicily. Exactly how many departed is unclear, but it is known that a substantial portion remained in the service of Frederick III and the administrative apparatus was still in place. However, the Sicilians had lost most of the commanders and more importantly, Roger of Lauria.