In response to Charles's retreat to Reggio, Peter III assembled a fleet in Messina to intercept the Angevin fleet as it traveled north through the Straits of Messina. James Perez the natural son of King Peter, had nominal command of the fleet, before it left for Collo, but for this operation, however, Peter of Queralt and Ramon of Cortada were placed in command. With only 15 galleys, the fleet sent to confront the Angevins was hardly an imposing force.

The Angevin fleet had the

advantage of numbers, but the fleet was a conglomerate of units from

Genoa, Pisa, Provence, and the Principato, and its men had very little

enthusiasm for a fight. The

main reason various units were reticent to engage the enemy was created by

Charles of Anjou

himself. Because of the relatively poor seaworthiness of

galleys, Mediterranean fleets were customarily dispersed and laid up

during the winter months to repair and refit the ships. After the Angevin

fleet retired to Reggio,

Charles dispersed units of the fleet to their

home ports. This resulted in a fleet  with no unity of command, composed of various units simply striving to

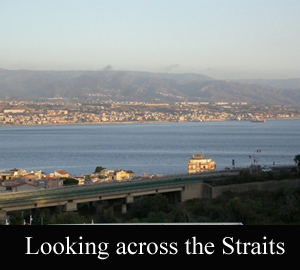

return home. Because the Strait of Messina is only 2.7 nm across at Messina,

each unit had to

pass within sight of the Aragonese fleet as it sailed north. This

weakness was not lost on King Peter.

Muntaner asserts that Peter described the Angevin fleet as "a

people who are fleeing and who have lost all heart, and ...are of many

nations and are never of one mind."

with no unity of command, composed of various units simply striving to

return home. Because the Strait of Messina is only 2.7 nm across at Messina,

each unit had to

pass within sight of the Aragonese fleet as it sailed north. This

weakness was not lost on King Peter.

Muntaner asserts that Peter described the Angevin fleet as "a

people who are fleeing and who have lost all heart, and ...are of many

nations and are never of one mind."

When the Angevin fleet attempted to pass north through the straits on October 11th, Aragonese galleys chased it back into port. Unfavorable winds held the fleet until October 14th, when it again attempted to pass through the strait. This time the Aragonese fleet caught the Angevin fleet at Nicotera. The battle that followed was dictated as much by the composition of the Angevin fleet as by any particular battle plan on the part of the Catalans and Aragonese. The chronicles are in virtual agreement that none of the groups within the Angevin fleet supported each other in the battle. At the advance of the enemy, they simply scattered without any resistance. The brunt of the attack was borne by the Pisans and the galleys of the Regno, which attempted to flee back to Nicotera. By the end of the day, 2 Pisan and 20 Angevin galleys were captured along with an assorted group of taridas and small vessels.

The battle was an unmitigated disaster for Charles. Not only did the enemy soundly defeat his fleet and capture a large number of warships and transports, the majority of galleys lost were those of the Regno. This rendered Charles's territories in Calabria defenseless. Realizing this, Peter launched raids into the region, followed in late October by an attack on Nicastro. Peter attempted unsuccessfully to cut off Charles's army stationed at Reggio, but continual raids and pressure led to the fall of Reggio on February 14, 1283. The Angevins were forced north to San Martino, but Peter was unable to break out of the peninsula and was effectively thwarted in his attempt to move up into the Regno.