With the English crown out of the picture, the papacy turned

again to Charles of Anjou.

By this time, Charles of Anjou was an extremely powerful member of the royal family.

Not only did he control the county of Anjou, but he had also solidified

control of Provence, which he had acquired through marriage. Louis IX was

hesitant and it was not until the arrival of the French pope, Urban IV,

that negotiations turned serious. Between 1262 and 1263 the pope

temporized, hoping to strike a peace with Manfred. However, by 1263 Urban

had decided that negotiations were futile and turned to Charles of Anjou

for support. The pope haggled for the best position he could get and came

to terms with Charles. Urban promised Charles the crown of the Kingdom of

Sicily, the preaching of a crusade against Manfred, and a promise by the

papacy to block any attempt by Conradin to become emperor. He also granted

Charles a three-year tithe on church revenues from France, Provence, and

the Kingdom of Arles, and more importantly guaranteed the loans made to

Charles by Italian bankers. In return, Charles promised to pay 10,000

ounces of gold annually to St. Peter and never to hold any office in

Imperial Italy or the Papal States. Moreover, under the agreement he could

not levy any taxes on the clergy and would have no say in ecclesiastical

appointments. Finally, Charles could be deposed by the pope and if so

could not demand any allegiance from his subjects thereafter.

temporized, hoping to strike a peace with Manfred. However, by 1263 Urban

had decided that negotiations were futile and turned to Charles of Anjou

for support. The pope haggled for the best position he could get and came

to terms with Charles. Urban promised Charles the crown of the Kingdom of

Sicily, the preaching of a crusade against Manfred, and a promise by the

papacy to block any attempt by Conradin to become emperor. He also granted

Charles a three-year tithe on church revenues from France, Provence, and

the Kingdom of Arles, and more importantly guaranteed the loans made to

Charles by Italian bankers. In return, Charles promised to pay 10,000

ounces of gold annually to St. Peter and never to hold any office in

Imperial Italy or the Papal States. Moreover, under the agreement he could

not levy any taxes on the clergy and would have no say in ecclesiastical

appointments. Finally, Charles could be deposed by the pope and if so

could not demand any allegiance from his subjects thereafter.

On the face of it, the agreement the Pope made with Charles in 1263 appeared highly favorable to the papacy, but sober reflection on the situation may have made Urban realize he made a deal with the Devil. Charles realized the situation that Urban was in and, when he was offered the senatorship of Rome in 1264, he used it as an excuse to renegotiate the agreement. Charles demanded a rewriting of the original agreement that would render it essentially meaningless. Urban had no choice but to acquiesce, but before the agreement could be finalized, Urban died in October 1264. The whole incident reveals that, despite apologies for him, Charles was not about to let his piety or scruples prevent him from bettering his position, even if it were at the expense of Holy See.

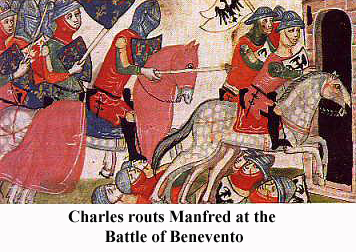

If Charles of Anjou was concerned by the death of Urban IV, he had no reason to be. In February 1265 the cardinals elected the French Cardinal of Sabina who took the name of Clement IV. He unreservedly adopted Urban's policies and urged Charles to begin his campaign immediately. On May 23, after having taken a ship from Marseilles to Ostia and alluding the fleet sent by Manfred to capture him, Charles entered Rome and was received by a jubilant crowd. Shortly afterwards he was invested with the Kingdom of Sicily. The appearance of Charles in Rome and his investiture not only took Manfred by surprise, but it also rallied the French nobility to Charles's cause. By October, Charles had assembled a formidable force in Provence which marched swiftly through northern Italy and past Rome while Manfred, finally prodded into action, came north with his army. On February 26, 1266 the two armies finally met at Benevento. After a closely fought battle, Charles emerged victorious with Manfred dead along with 3,000 of the original 3,600 horsemen who went into battle with him. Among the dead at Benevento was the Baron Lauria. It is doubtful if Charles even knew of this or would have particularly cared, but in fact that death would set in motion a series of events which would create one of Charles's most implacable and talented foes.