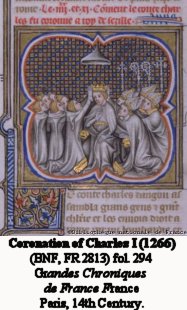

The victory at Benevento

proved a windfall for Charles

of Anjou. He quickly  moved to assert his authority and by 1267 had firm control of the Piedmont

in the north, while Florence recognized him as its overlord. With the

support of the Guelf party, his influence in Lombardy and Tuscany

increased to the point he was able to extract favorable loans from the

bankers in the region. In the Kingdom of Sicily Charles approached the new

acquisition much in the same manner he had his inheritance of Provence.

moved to assert his authority and by 1267 had firm control of the Piedmont

in the north, while Florence recognized him as its overlord. With the

support of the Guelf party, his influence in Lombardy and Tuscany

increased to the point he was able to extract favorable loans from the

bankers in the region. In the Kingdom of Sicily Charles approached the new

acquisition much in the same manner he had his inheritance of Provence.

Custom dictated that a new ruler call the parliament of the barons and the people at Palermo and go through the pro forma act of being elected. Charles ignored this and simply sent in an army of adventurers and freebooters who proceeded to plunder areas that refused to support him. In fact, he would only visit Sicily once when returning to Naples from the 1271 crusade to Tunis. The island was divided along family and municipal lines and many used Charles's intervention to settle old scores. In the end, large parts of the island were ravaged and several cities looted, including Augusta, which was burned to the ground by the invaders with the help of Messina citizens.

The Angevin forces were followed by Angevin administrators who

rapidly took over the existing governmental structure. Charles's

ambitions required large sums of money, and he was determined to extract

it as efficiently as possible. Charles did not change the

Norman-Hohenstaufen governmental structure but instead left it intact and

simply ran it with an efficiency that the populace had never experienced

before. Almost immediately, Charles set about examining the titles of all

of the nobility on the island. One of the concessions that he had obtained

from the Pope was that all lands and titles granted by Frederick II and

Manfred were invalid and the lands would be forfeit to Charles. Families

that either received their grants from the Hohenstaufens or who could not

produce their original deeds were forced off their ancestral lands and

replaced by Angevins, while families with clouded titles had to pay

extortionate sums of money to retain their holdings.

The Angevin forces were followed by Angevin administrators who

rapidly took over the existing governmental structure. Charles's

ambitions required large sums of money, and he was determined to extract

it as efficiently as possible. Charles did not change the

Norman-Hohenstaufen governmental structure but instead left it intact and

simply ran it with an efficiency that the populace had never experienced

before. Almost immediately, Charles set about examining the titles of all

of the nobility on the island. One of the concessions that he had obtained

from the Pope was that all lands and titles granted by Frederick II and

Manfred were invalid and the lands would be forfeit to Charles. Families

that either received their grants from the Hohenstaufens or who could not

produce their original deeds were forced off their ancestral lands and

replaced by Angevins, while families with clouded titles had to pay

extortionate sums of money to retain their holdings.

The coin struck by Charles in Sicily reads on the top face: "Charles, thanks to the grace of God, King of Sicily". The reverse side reads: "Duchy of Apulia" and "Principality of Capua" (Musée des Médailles, Courseulles-sur-Mer, France).

Charles also began to impose the 'general subvention' on a regular basis without asking for permission from the parliament to impose the hated tax. The 'general subvention' had been imposed on a regular basis under Frederick II, so technically what Charles was doing was not different. However, he collected the taxes with a fervor previously not experienced by the population and even began to employ forced loans. It is true that Charles undertook a number of reforms, rebuilt roads and harbors, and undertook policies to stimulate trade, but these were designed to benefit the treasury by generating more revenue, and in any case virtually all of the improvements were made on the mainland, not in Sicily. In trying to pay his debts to the Tuscan bankers and to finance his new projects, Charles was alienating virtually every segment of Sicilian society, even those who initially supported him.