The botched evacuation from Messina and the subsequent Battle of Nicotera had been a blow to Charles. Not only had he lost most of the galleys from the Regno, but he had also discovered that his erstwhile allies could not be counted on in a close fight. These lessons had not been lost on him, and he set about assembling a fleet composed entirely of his French subjects. Realizing that only by controlling the waters around Apulia, Calabria and Sicily did he have a chance of recovering his territories, Charles wrote to the seneschal of Provence from Reggio in November 1282 and ordered him to assemble a fleet composed entirely of men and ships from southern France. 20 well-armed galleys and 2,000 crossbowmen and spearmen were to assemble at Marseilles. Charles chose two men from Marseilles to command the fleet, Bartholome Bonvin and William of Cornut, the latter of who later swore an oath to bring back Roger of Lauria dead or alive.

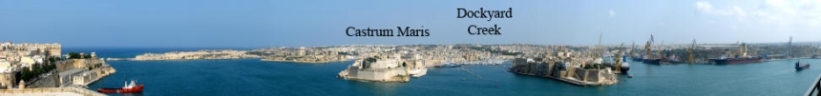

Sometime in late April or early May the Provençal fleet sailed for Naples where it received orders from the prince of Salerno, Charles's son, to proceed to Malta to relieve the garrison at the Castrum Maris at the Grand Harbor. The French garrison had been bottled up in the castle from the outset of the war by a general insurrection, which was later bolstered by a contingent of Aragonese under Manfred Lancia. Malta lay in a strategic position, and both sides were anxious to control it.

The Provençal fleet arrived at

Malta on June 4th and anchored in Dockyard Creek in the Grand Harbor.

Supported by the new arrivals, the garrison forced Manfred Lancia to

retreat, but this proved to be only a temporary success for the French.

Roger of Lauria had received news of the French fleet in Sicily and had

set out in pursuit with 21 galleys, arriving at Gozo on the evening of

June 7th. On hearing that the Provençal fleet was at Malta, he moved that

same night to the Grand Harbor and in the morning challenged the French to

battle. Despite the apparent parity between the two fleets, the result of

the fight was another disaster for Charles of Anjou.

The battle lasted until dusk, when Admiral Bonvin broke free and

fled out to sea with 7 galleys, leaving the other galleys to their fate.

But even these galleys were so damaged and the crews so depleted that

two had to be abandoned and sunk.

forced Manfred Lancia to

retreat, but this proved to be only a temporary success for the French.

Roger of Lauria had received news of the French fleet in Sicily and had

set out in pursuit with 21 galleys, arriving at Gozo on the evening of

June 7th. On hearing that the Provençal fleet was at Malta, he moved that

same night to the Grand Harbor and in the morning challenged the French to

battle. Despite the apparent parity between the two fleets, the result of

the fight was another disaster for Charles of Anjou.

The battle lasted until dusk, when Admiral Bonvin broke free and

fled out to sea with 7 galleys, leaving the other galleys to their fate.

But even these galleys were so damaged and the crews so depleted that

two had to be abandoned and sunk.

While the loss of warships would cripple the Angevin naval operations until they could be replaced, the French had incurred another loss that would be more difficult to remedy. Muntaner claims that 3,500 Angevin were slain and that, "between the wounded and other which had hidden below, there were only five hundred left alive, and of those many died afterwards because of their mortal wounds." More important is Desclot's comment on the effect of the battle on the population of Marseilles: "And that they [the people of Marseilles] had such pain is not a marvel, for there was no one which had not lost a son, a father, a brother, a husband or relative." Given that the evidence indicates Angevin losses were between 3,500 and 4,000, Desclot's assertion is not an exaggeration given that the population for Marseilles and its surrounding environs was approximately 20,000 at the end of the thirteenth century. The defeat at Malta was nothing short of catastrophic for the population. Not only had the community lost nearly twenty percent of its population, it had been a very selective loss, restricted to the able-bodied male population. Costing the Angevins the lives of Admiral Cornut and his kinsmen, it had effectively stripped Marseilles and Provence of its best naval personnel. The extent of the loss and its crippling effects would become apparent in two years. For more on the battle and its consequences see The Battle of Malta: Prelude to a Disaster article.