In the spring of 1284

Roger of

Lauria followed up his success at Malta with a series of devastating raids

up the coast of Calabria and at Naples. More

importantly, he captured the offshore

islands of Ischia and Capri, which

he used as bases to intercept shipping trying to enter or exit

Naples.

The capture of the islands also allowed Roger to monitor the

progress of the fleet being readied for the crusade called against the Crown of Aragon. The blockade was

devastating to the Neapolitan merchant community and Charles of Salerno,

son of Charles of Anjou, was undoubtedly under pressure to lift it.

However, the papal legate, Cardinal Gerard, reminded the young prince that

he was

under orders from his father to avoid a confrontation with the

Aragonese-Catalan fleet. It

was good advice for Charles of Anjou had built another fleet at Marseilles

and was preparing to sail south to join with the squadron at Naples. If

the two fleets could join, then the Angevins would be able to decide the

outcome by sheer numbers.

was good advice for Charles of Anjou had built another fleet at Marseilles

and was preparing to sail south to join with the squadron at Naples. If

the two fleets could join, then the Angevins would be able to decide the

outcome by sheer numbers.

Roger was aware of the

situation and the raids he had undertaken may have been an attempt to

bait Charles of Salerno into open battle. Roger had

between 36 and 40 galleys, while the estimates of the Angevin

fleet range from 28 to 70. Based on the accounts and Angevin documents it

appears that Angevin fleet was between 30 and 40 ships with

another 34 galleys coming south with Charles of Anjou.

The capture of 2 Neapolitan galleys returning to Naples with news

of the imminent arrival of the Provençal fleet gave urgency to the need

to engage the Regno fleet. In a final attempt to draw

Charles of Salerno

out, Roger split his fleet and made a show of the larger portion sailing

south to Sicily when in fact it circled back to join Roger once out of

sight of land. Whether it was the prospect of being able to descend on an

inferior fleet, pressure from the Neapolitan merchants, or youthful pride,

Charles made the fateful decision to engage the Aragonese fleet on June 5,

1284. While the Prince of Salerno was eager to put out to sea, his sailors

and knights had second thoughts about fighting Roger and his

Catalan-Sicilian crews. According to the chronicles, Charles had to shame

his knights and barons into following him into the galleys, while the

crews were apparently forced at sword point to embark.

After setting sail, in pursuit of what was perceived to be the remnants of the Aragonese squadron the Angevin fleet was soon confronted with the entire fleet. At the sight of the enemy galleys, the Neapolitan galleys fled back to Naples, leaving the 10 Provençal galleys of the squadron, and Charles, to fend for themselves. The battle ended swiftly with the capture of Charles of Salerno, the 10 galleys and a large number of the Neapolitan nobility. An unqualified success for Roger of Lauria and his fleet, the battle delayed Charles of Anjou's plans, provided the Aragonese fleet with much needed galleys, and gave the Crown some very valuable hostages. Following the battle, Roger sailed to Naples and demanded and received the release of the Lady Beatrice, who was the daughter of King Manfred and the sister of the Queen of Aragon from the Castello do Ovo. Shortly afterwards, the city of Naples rose in revolt with the reported cry of "Long live Roger of Lauria and Death to Charles!" Charles arrived three days later and on hearing of the loss of the fleet and his son exclaimed, "O Great King, King of Kings, and Lord of Lords, is this the end you give to all our labors?" Undoubtedly, Charles wished to pursue Roger, but the situation in Naples demanded his immediate attention. Charles wanted to sack the city in retribution for its revolt and the cowardice of its galleys, but the papal legate dissuaded him. In any case, it appears that Charles was more interested in maintaining his authority in the Regno than immediately engaging Roger or regaining his eldest son, whom he referred to as a "fool". As it was, once Charles of Salerno was brought to Messina, only the intervention of Queen Constance prevented an angry mob from lynching the prince.

Nonetheless, regardless of the defeat, the overall strength of the Angevin fleet had been hardly affected. The majority of the fleet had returned safely to Naples, and with the arrival of the Charles of Anjou the combined force was so overwhelming that Roger had to flee the area.

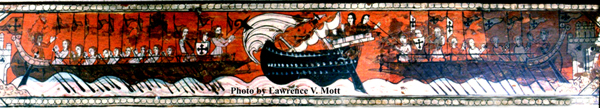

Photograph of the painting by Ramon Tusquets is courtesy of the Institut Amatller d'Art Hispanic in Barcelona.