Charles of Anjou appears to

have taken the first reports of the Sicilian revolt as lightly as the

Governor of Sicily had.

He sent 2 galleys from Amalfi

to support the blockade of Palermo which was

ineffectually enforced by the Messinese galleys. When word of the uprising

at Messina reached the squadron, the Messinese galleys turned on the

others and two of the Amalfian galleys were captured.

When word finally reached Naples that the entire island, including

Messina, had revolted, Charles flew into a rage and swore to lay waste to

the towns that had revolted and slaughter the population as an example.

Charles had every reason to be distraught over the recent events.

What he had perceived to be a minor uprising at Palermo was suddenly a

full-scale revolt, which did not just delay his expedition against the

Byzantine Empire, but crippled it. Not only did Charles have to face his captured

galleys, now armed and manned by the Messinese rebels,

but he lost arms and stores that he amassed at Messina for his expedition

against the Byzantine Empire.

ineffectually enforced by the Messinese galleys. When word of the uprising

at Messina reached the squadron, the Messinese galleys turned on the

others and two of the Amalfian galleys were captured.

When word finally reached Naples that the entire island, including

Messina, had revolted, Charles flew into a rage and swore to lay waste to

the towns that had revolted and slaughter the population as an example.

Charles had every reason to be distraught over the recent events.

What he had perceived to be a minor uprising at Palermo was suddenly a

full-scale revolt, which did not just delay his expedition against the

Byzantine Empire, but crippled it. Not only did Charles have to face his captured

galleys, now armed and manned by the Messinese rebels,

but he lost arms and stores that he amassed at Messina for his expedition

against the Byzantine Empire.

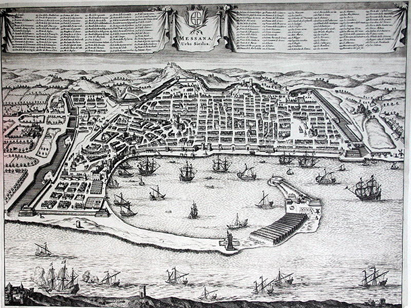

After expelling the French from Messina, the newly-elected officials sent a Genoese merchant with news of the revolt to the Byzantine emperor, not the court of Aragon. Considering the Byzantine navy was in no position to intervene, it is hard to imagine what help the Sicilians expected, but the action provides strong evidence that the Sicilians believed their main support was coming from the East. Messina, Corleone, and Palermo declared themselves independent communes and initially made no appeal for outside intervention.

A different pope might have avoided the long bloody war that was to follow. From the outset, the Sicilian towns hoped that they could obtain freedoms similar to those enjoyed by the mainland communes by appealing directly to the Holy See for protection. Even before the open revolt in late March, two legates went to Pope Martin IV (right) to beg for relief from the Angevin oppression, but were rebuffed. Following the uprising, Palermo sent another emissary to Martin to ask for his protection, but he refused to see them. He also rejected the appeals of another mission from Palermo and Messina in May. The rejection of the Sicilians' pleas for protection was followed by a bull excommunicating the population of Sicily on May 7th. Another pope may have seen the opportunity to free the papacy from Charles, but Martin, a former member of the royal French household and installed as pope through the Charles's intervention, was a creature of the Angevins.

With the loss of Messina (left), Charles quickly assembled a fleet and moved to Catona across the Straits from Messina. Estimates of its size range from 80 to 140 galleys with assorted support vessels. Against this, the Messinese mustered only 30 galleys and Charles crossed and landed north of the city on July 25th. Both Charles and Pope Martin IV apparently hoped that the show of force would be enough to intimidate the Messinese into surrender. Instead, they faced stiff resistance from the city. Starting August 6th, Charles undertook a series of attacks that the city easily repulsed. A papal legate, Cardinal Gerard, was sent to the city to demand its surrender, and the Messinese initially agreed on the condition that the Pope would be their protector. Learning that the city would be returned to Charles, they rejected the terms and expelled the legate. The newly-declared communes' attempts to place themselves under papal protection indicate no initial strong groundswell of support for Peter III of Aragon to become king. The population wished to avoid further foreign intervention if possible. Despite repeated attacks lasting into September and offers of general clemency, the Messinese refused to capitulate if they would return to Angevin control. Charles settled in for a long siege, but time was not on his side.