In the spring of 1282, Charles of

Anjou was prepared to conquer of Constantinople. He gathered a large force from

throughout the Regno and a large portion of the invasion fleet lay at anchor in

Messina awaiting orders to set sail sometime in April. Charles was obviously

aware of the preparations of Peter III,

but appears to have discounted the

threat posed by the Aragonese-Catalan fleet. Surviving correspondence does not

suggest that Charles threatened or tried to parley with the Crown of Aragon

concerning Peter's intentions. He may have expected the threat of French or

papal intervention to dissuade Peter from any adventurism in Sicily, but neither

of Charles's benefactors threatened Peter until problems arose on the island.

Likewise, Charles seems to have been completely unaware of the growing hostility

of the Sicilian population to Angevin rule. In fact, the heavy taxation and the

abuse of power by local authorities had brought public sentiment to the boiling

point. Moreover, John of Procida

and others had been working hard in Italy and Sicily to forment revolt.

Only a small provocation would be needed to set off an explosion of public violence.

Virtually all of the chronicles agree about the incident that led to the revolt. On March 29, 1282, as a group of noble women approached the Church of the Holy Spirit (left) in Palermo, several Angevin soldiers confronted them. On the pretext of searching for hidden arms, the soldiers molested the women in front of their families. The open insult to the women and the contemptuous attitude of the Angevins were too much for the onlookers. With the cry "Death to the French!" the people set on the soldiers and other Angevins in the city and slaughtered them. The chronicles are either silent or contradictory on the exact time of the revolt, but tradition placed the event when the church bell rang for vespers. This is the source of the name Revolt of the Sicilian Vespers, though it did not come into use until the fifteenth century. Corleone soon followed Palermo, and on April 3rd the two cities declared themselves communes and sent messengers to other cities with news of the revolt. The uprising spread quickly to most parts of the island and lead to the widespread massacre of anyone French, regardless of sex or age.

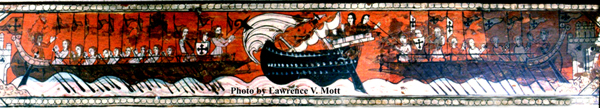

Distance and the large fleet massed in the harbor kept Messina from revolting, even after a letter dated April 13th arrived from Palermo asking for the city's support against the Angevins. Though they knew of the uprising, Angevin authorities in Messina seem to have underestimated the seriousness of the revolt. Their initial response was to send 7 galleys under a Captain Riccardo Riso to quell the uprising at Palermo. Arriving at Palermo, the galley crews sided with the rebels and refused to fight. Messina eventually rose up against its oppressors, and on April 29th the city population revolted, forcing the Angevin garrison into the Castle of Mategriffon and seizing the fleet that lay in the harbor. The Governor of Sicily, Herbert of Orléans, and the garrison were allowed to leave on the condition that they sail directly to Aigues-Mortes in France. Leaving the harbor, Herbert sailed directly to Catona across the Straits in order to organize a counterattack.